Part 2: Making a strategy more “digital”

Part 1 presented symptoms that arise in the process of implementing product strategies that aren’t “digital” enough—meaning that they don’t effectively anticipate or address the emerging needs of product managers and teams. If any of these symptoms are familiar to you and your team, it’s worth discussing how the product strategy might be strengthened to alleviate them.

Did We Go Wrong, or Just Not Far Enough?

A product strategy may have issues simply because it is unintentionally biased by the focus and experience of those who are tasked with formulating it. A CDO may bring a very high degree of “digital” influence to the strategy, but may lack pragmatic experience building and delivering a variety of products types at scale. Whereas a CPO may produce a very thorough focus on the “What” and “Why” but insufficiently factor the impact of changes in the “How” that will affect the performance of the product organization as they implement the strategy.

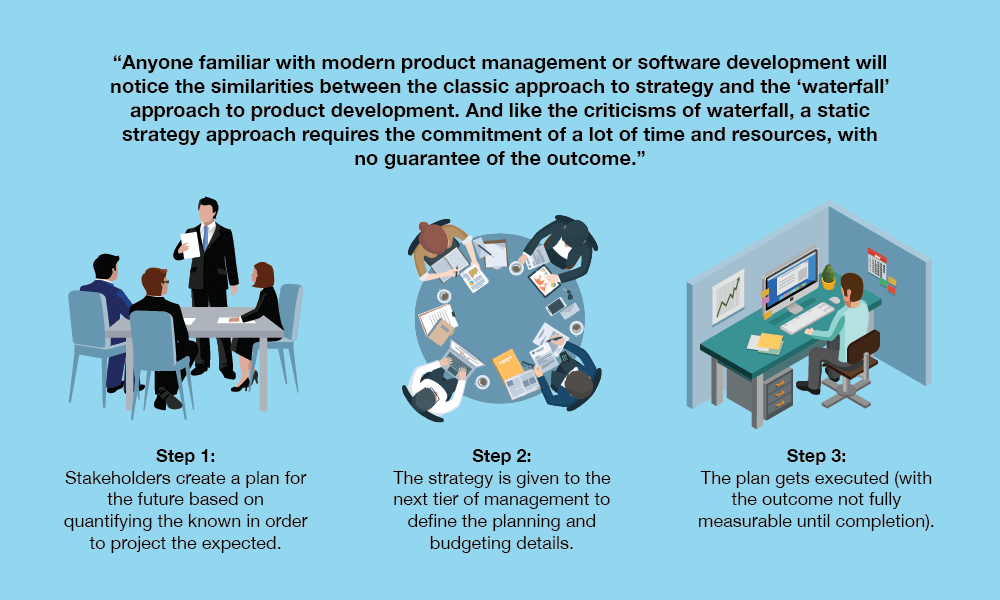

A strategy is often made less effective simply because its approach has been too cookie-cutter. Strategy, in a business context, is a tool for planning, consensus-building, and direction-setting among the executive management. The classic approach to strategy is that stakeholders (often with consultants) articulate a plan for the future — based largely on quantifying the known in order to project the expected — and then make decisions about the future. This strategy is given to the next tier of management to define the details, align budgets, and plan for resources and operational details. After the planning and budgeting cycle is done, the plan gets executed, with the outcome not fully measurable until completion.

Another characteristic of strategies is the urgency surrounding them, often expressed as a reticence to get feedback or analyze decisions and assumptions— we already have buy-in, just get going. This can reflect the challenge of building consensus and getting buy-in, especially where there’s a high degree of uncertainty or disagreement about the future. It may also be a tacit signal that there is a gut-level awareness that the strategy is incomplete or is glossing over some potential show-stopping issues, but it’s politically or culturally unacceptable to dissent.

Just because a product strategy has been produced and agreed to doesn’t mean it is correct or will be effective. And just because a product strategy isn’t all it should be doesn’t mean it can’t be improved.

Killing Zombies: Bringing a Product Strategy to Life

Static strategies can make a product organization or even a business look like a zombie — making mistake after mistake, completely unaware, and oblivious to anything except what the strategy dictates.

Strategies can become static if they are only used as an initial stage gate, if they provide little to no ongoing value, or if they lose relevance as time goes by because too many things have changed. Strategies are inherently static if they don’t acknowledge, allow for, and facilitate the adoption of changes — especially at levels that are clearly changing or where there is a high degree of uncertainty. Strategies need to be at least as dynamic and evolving as the context to which they are applied.

The goal is to be sure that the strategy doesn’t get stuck in the initial gate, but instead becomes a tool that remains useful. If there is a growing gap between what your product strategy said and what is actually happening, people should be asking: Was the product strategy missing some key points? Are we still actually following a strategic path or are we just bushwhacking?

A static approach can be made more dynamic—brought to life— in 3 ways (and ideally all three would be integrated as part of an ongoing product strategy function):

- A systematic effort to identify, understand, and then categorize issues, risks, and areas of uncertainty

The point here isn’t to overload the strategy with details, or hope to address everyone’s concerns. Since every strategy has to be operationalized and tactically implemented, understanding the categories (and size) of issues, risks, and uncertainties along that path, in advance, gives a better picture of which things are likely to have a broader effect and should be explicitly addressed in the product strategy. This doesn’t mean there will always be a clear answer/decision. However it allows everyone affected to be aware of the issues, options, and current thinking behind how to address them. - A systematic effort to identify how success/failure of product(s) could influence overall success of the product strategy (i.e., develop a portfolio approach)

By understanding the business value of platform capabilities and products, and potential risks to delivery and market adoption (and impact on expected ROI), potential pivot points and shifts in priority can be identified as options earlier in the planning cycle and better managed. A portfolio approach starts with the idea that not all products are equal because: -

- How you measure value varies across capabilities, products, or features. Some may be of low-value for near-term revenue, but instrumental for building competitive advantage. Some products may require market-building in order to scale or only be viable as part of a broader solution

- Different approaches to product development have different requirements. De-risking through an MVP approach assumes a product that will evolve through a feedback cycle, revealing dynamics that can’t be predicted today.

The idea behind a portfolio approach is that is that there is no sure bet on future outcomes. Knowing what you will measure and how you will interpret findings in advance means you are more likely to actually do it and be able to make smart decisions.

- De-risking by looking for the important “unknown knowns” before planning and budgeting initial implementation programs

There is often useful information available that gets ignored because it doesn’t seem relevant enough to the situation at hand. Sometimes this bias occurs without anyone really being aware of it, because it’s built into the approach to strategy development.

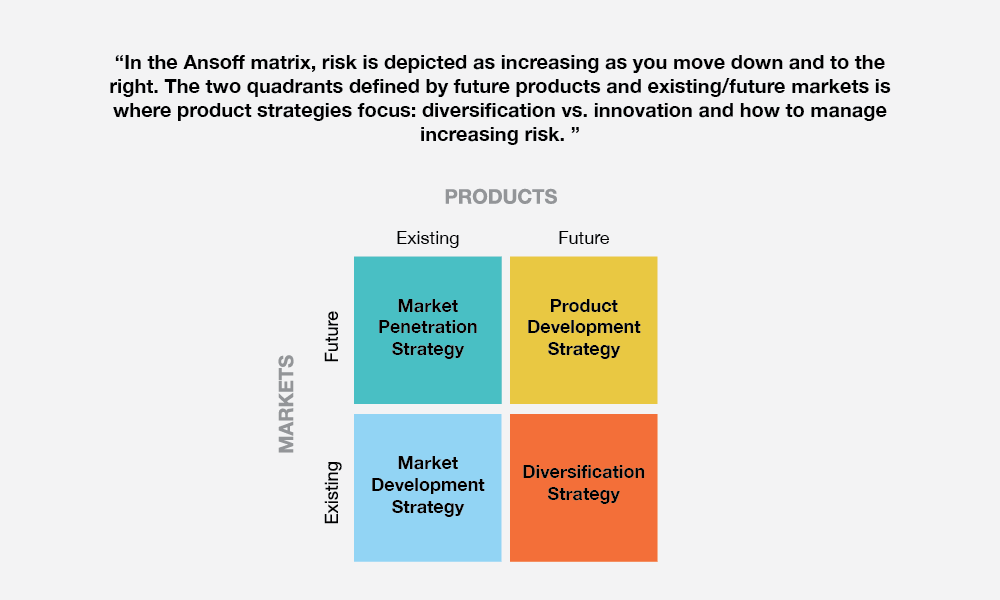

For instance, a common tool used in growth planning is a framework called the Ansoff matrix. It’s a 2 x 2 with the horizontal axis representing existing and future products, and the vertical axis representing existing and future markets.

Right out of the gate, the focus shifts away from the other quadrants. They haven’t become suddenly less relevant, yet what they might imply is often assumed as not relevant to forward-looking product strategy. However, those in charge of product strategy can pull a clever trick: they can simply decide to make those other quadrants relevant by looking at them as inputs and exploring relationship scenarios between quadrants over time as a product strategy would be put in play. This will lead to questions that the strategy should seek to confirm as relevant/irrelevant, and when relevant, explain why, and based on what decisions and implications.

The goal is two-fold: (1) make sure there aren’t unstated assumptions being made by other areas of the business about what the product strategy is unaware, and (2) make sure project strategy doesn’t inadvertently miss key interdependencies. The following questions are examples taking this kind of approach when using the Ansoff matrix:

-

- What changes in how we currently do business will be needed when we are delivering future products for existing and future customers and to what degree do our product bets assume this will occur?

- What’s the risk to the product strategy if these changes (in how we do business) don’t happen as planned, or in lock-step with the product strategy implementation?

- Can we de-risk this in how we define, plan, and launch products, and if so, where and how?

- Are we expecting existing customers to eventually migrate to new products? If so why, and can they continue to use existing products as they adopt new ones? What does this imply for our product strategy in terms of product adoption requirements/legacy support requirements?

- Will existing products be relevant to new customers?

- How much do we know about additional needs of our current customers?

- How much do we know about needs of our future customers?

- What changes in requirements for new products and requirements of new customers would likely make our current approach to product management, (definition, development, and deployment) inefficient or unsuccessful?

Conclusion

There may be some reluctance to re-approaching a product strategy that has already been approved or is well underway. Every business needs to consider the kinds of issues they are facing and weigh the costs and benefits of a bespoke solution (i.e., fix it in a product-by-product context) or holistic solution (i.e., address it at a product strategy level). In either case, at least understand what issues can be addressed earlier and how you can improve subsequent strategy exercises. Taking a more considered approach to measuring the effectiveness of the strategy as it is implemented can also begin to shift the overall mind-set away from static strategies, and enable more flexible strategies that provide more value to the teams who implement them.